Modern c++ tools and techniques

Intro

This post is a summary of a talk I gave at work. It discuses some useful c++ techniques and tooling that will help you become a more effective software engineer. All code is available on Github.

Some of the basic ideas in this post are taken for the fantastic book The Effective Engineer:

- Optimize for learning

- Fast iteration

- Good abstractions

- Master your craft

Design patterns and techniques

The first thing to mention is to just design new stuff when you absolutely have too. See what’s available before starting your own design.

Boost and generally anything coming out of Google, Facebook etc. are good options.

If you have to design something from scratch using design patterns usually makes your software cleaner and more extensible. In software engineering, a design pattern is a general reusable solution to a commonly occurring problem. I’m gonna introduce some basic design patters that have proven quite useful.

Design Pattern: Factory

In class-based programming, the factory method pattern is a creational pattern that uses factory methods to deal with the problem of creating objects without having to specify the exact class of the object that will be created. This is done by creating objects by calling a factory method rather than by calling a constructor.

As an example, let’s say we have a class to read files. We can create an interface for reading files and then create 2 classes to read local files and files from HDFS. The interesting part is that the client code can work with any file reader. In the future we can implement new protocols or improve existing implementations without changing the client code. We can also change the type of object we create at runtime (e.g. using environment variables).

class Reader {

public:

virtual ~Reader() {}

virtual void read() = 0;

};

class LocalReader : public Reader {

public:

void read() {

std::cout << "Reading from local FS" << std::endl;

}

};

class HdfsReader : public Reader {

public:

void read() {

std::cout << "Reading from HDFS" << std::endl;

}

};

class ReaderFactory {

public:

static std::unique_ptr<Reader> makeReader(const std::string& type) {

if (type == "local") {

return std::unique_ptr<Reader>(std::make_unique<LocalReader>());

}

else if (type == "hdfs") {

return std::unique_ptr<Reader>(std::make_unique<HdfsReader>());

}

else {

throw std::runtime_error("Unsupported type");

}

}

};

int main() {

auto reader1 = ReaderFactory::makeReader("local");

reader1->read();

auto reader2 = ReaderFactory::makeReader("hdfs");

reader2->read();

}Design Pattern: Observer

The observer pattern is a software design pattern in which an object, called the subject, maintains a list of its dependents, called observers, and notifies them automatically of any state changes, usually by calling one of their methods. It is mainly used to implement distributed event handling systems.

When an event happens (in this example when we consume a line), we notify all the observers.

using GenericMap = std::unordered_map<std::string, boost::any>;

class INotifiable {

public:

virtual ~INotifiable() {}

virtual void onEvent(const GenericMap& data) const = 0;

};

class EventLogger : public INotifiable {

public:

void onEvent(const GenericMap& data) const {

const std::string& text = boost::any_cast<std::string>(data.at("text"));

std::cout << text << std::endl;

}

};

class Reader {

public:

void addObserver(INotifiable* observer) {

observers_.push_back(observer);

}

void read() const {

GenericMap map;

map["text"] = std::string("FYI");

for (auto i : boost::irange(0,1)) {

for (auto observer: observers_) observer->onEvent(map);

}

}

private:

std::vector<INotifiable*> observers_;

};

int main() {

EventLogger ev1;

EventLogger ev2;

Reader r;

r.addObserver(static_cast<INotifiable*>(&ev1));

r.addObserver(static_cast<INotifiable*>(&ev2));

r.read();

}Design Pattern: Decorator

In object-oriented programming, the decorator pattern (also known as Wrapper) is a design pattern that allows behavior to be added to an individual object, either statically or dynamically, without affecting the behavior of other objects from the same class. Decorators are useful to add access control, logging, locking, to make a class thread safe etc.

class IDownloader {

public:

virtual ~IDownloader() {}

virtual void download() = 0;

};

class SimpleDownloader : public IDownloader {

public:

void download() {

std::cout << "Downloading ..." << std::endl;

}

};

class LoggingDownloader : public IDownloader {

public:

LoggingDownloader(std::unique_ptr<IDownloader> downloader) {

downloader_ = std::move(downloader);

}

void download() {

std::cout << "begin log" << std::endl;

downloader_->download();

std::cout << "end log" << std::endl;

}

private:

std::unique_ptr<IDownloader> downloader_;

};

int main () {

auto simpleDownloader(std::unique_ptr<IDownloader>(std::make_unique<SimpleDownloader>()));

auto loggingDownloader(std::unique_ptr<IDownloader>(std::make_unique<LoggingDownloader>(

std::unique_ptr<IDownloader>(std::make_unique<SimpleDownloader>()))));

simpleDownloader->download();

loggingDownloader->download();

}So far we’ve talked about design patterns. Now I’d like to switch gears and talk about some techniques.

Technique: Smart pointers

Memory management in c++ is hard. It’s easy to forget a delete or make a mistake about the lifetime of object and introduce a memory-related bug.

Smart pointers alleviate many of the problems with ‘raw’ pointers, mainly forgetting to delete the object and leaking memory, even in the presence of exceptions. There are many types of smart pointers but the main ones are unique_ptr and shared_ptr for unique and shared ownership respectively.

class A {

public:

~A() {

std::cout << "In destructor" << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

auto ptr1(make_unique<A>());

// auto ptr2 = ptr1; // doesn't compile

auto ptr3(make_shared<A>());

std::cout << ptr3.use_count() << std::endl;

auto ptr4 = ptr3;

std::cout << ptr3.use_count() << std::endl;

}Technique: c++11/14 features

c++11 and 14 bring useful new language features. Some of the most interesting ones are:

- auto: less typing

- lambda: ability to define functions inside other functions.

- move semantics: avoids copies, higher efficiency

- …

int main() {

auto myvec = {“hola”,”adios”};

cout << myvec.size() << endl;

auto anothervec = std::move(myvec);

atomic<uint64_t> counter;

counter.store(0);

auto incr = [&] () {

for (auto i : boost::irange(0,1000000)) {

++counter;

}

};

thread t1(incr);

thread t2(incr);

t1.join();

t2.join();

cout << counter.load() << endl;

return 0;

}Technique: boost any/variant

Variants offer a simple solution for manipulating an object that can hold different types in a uniform manner. Whereas standard containers such as std::vector may be thought of as “multi-value, single type,” variant is “multi-type, single value.”

class LoggingVisitor : public boost::static_visitor<>

{

public:

void operator()(const int& i) const {

cout << "Visiting int" <<endl;

}

void operator()(const string& str) const {

cout << "Visiting string" <<endl;

}

};

int main() {

boost::variant<int,std::string> variant1 = 6;

auto int1 = boost::get<int>(variant1); // ok

try {

auto str1 =

boost::get<std::string>(variant1); //fails

}

catch (const boost::bad_get& e) {

std::cout << "fails" << std::endl;

}

boost::apply_visitor(LoggingVisitor(), variant1);

boost::variant<int,std::string> variant2 = "hola";

boost::apply_visitor(LoggingVisitor(), variant2);

}If your function needs to return any type use boost::any. The advantage of boost::any vs a void * pointer is type safety.

#include <boost/any.hpp>

int main() {

boost::any any1(static_cast<uint64_t>(0));

uint64_t int1 = boost::any_cast<uint64_t>(any1); // ok

boost::any any2(static_cast<uint64_t>(0));

try {

int int2 = boost::any_cast<int>(any2); // fails

}

catch (const boost::bad_any_cast& e) {

std::cout << "fail" << std::endl;

}

}With this we conclude the design section. The following sections gives an overview of some useful c++ tools.

Tools

Clang

Clang is a nice alternative to g++. It gives you faster compilation times and more meaningful errors.

It also comes with many useful tools that we’ll explore in later sections.

Use cmake/scons for building

Instead of using raw Makefiles you can use something more modern like Cmake or Scons.

Those tools give you cross-platform builds, automatic discovery and configuration of the toolchain, automatic dependency management, debug/release modes and many other useful features.

I’m not saying all those things can’t be done with make, but that involves a significant effort.

Debugging

Probably you’ll spend a lot of time debugging so being familiar with GDB it’s very important. Oftentimes you’re better off with a graphical debugger that uses GDB under the hood.

Testing with Google Test

Testing is a high leverage activity. It ensures the system is working as expected and gives you confidence to add new features or make changes.

Test small functionality with unit testing and have integration and performance testing as well.

class Calculator {

public:

static uint64_t sum(const uint64_t op1, const uint64_t op2) {

return op1 + op2;

}

static uint64_t mul(const uint64_t op1, const uint64_t op2) {

return op1 * op2;

}

};

struct MyConfig {

MyConfig(const uint64_t op1,

const uint64_t op2) : op1_(op1), op2_(op2) {

}

const uint64_t op1_;

const uint64_t op2_;

};

::std::ostream& operator<<(::std::ostream& os, const MyConfig& config) {

return os << "op1: " << config.op1_ << " op2: " << config.op2_;

}

class MyTest : public ::testing::TestWithParam<MyConfig> {

};

TEST_P(MyTest, Sum) {

const MyConfig& conf = GetParam();

EXPECT_EQ(Calculator::sum(conf.op1_,conf.op2_), conf.op1_ + conf.op2_);

}

TEST_P(MyTest, Multiply) {

const MyConfig& conf = GetParam();

EXPECT_EQ(Calculator::mul(conf.op1_,conf.op2_), conf.op1_ * conf.op2_);

}

INSTANTIATE_TEST_CASE_P(MyValues, MyTest, ::testing::Values(

MyConfig(1,2),

MyConfig(3,4)

));Some useful Google Test tips are:

- Use parameterized tests

- Run only some tests with

--gtest-filter=<pattern> - List all tests:

--gtest_list_tests - Exclude certain tests by prepending

DISABLED_to the test name

Mocking

Mocks are useful when you want to test a component but its dependencies haven’t been implemented yet or if the dependencies are complex to set up (e.g. an external HTTP service).

#include <gmock/gmock.h>

#include <gtest/gtest.h>

class ICalculator {

public:

virtual uint64_t sum (const uint64_t op1, const uint64_t op2) = 0;

virtual uint64_t mul (const uint64_t op1, const uint64_t op2) = 0;

};

class OnlineCalculator : public ICalculator {

public:

uint64_t sum(const uint64_t op1, const uint64_t op2) {

throw std::runtime_error("Unimplemented");

}

uint64_t mul(const uint64_t op1, const uint64_t op2) {

throw std::runtime_error("Unimplemented");

}

};

class MockCalculator : public ICalculator {

public:

MOCK_METHOD2(sum, uint64_t(const uint64_t, const uint64_t));

MOCK_METHOD2(mul, uint64_t(const uint64_t, const uint64_t));

};

TEST(testcase, test) {

using ::testing::Return;

using ::testing::_;

MockCalculator c;

EXPECT_CALL(c, sum(_,_)).Times(2).WillOnce(Return(3)).WillOnce(Return(7));

EXPECT_CALL(c, mul(_,_)).Times(2).WillOnce(Return(2)).WillOnce(Return(12));

EXPECT_EQ(c.sum(1,2), 3);

EXPECT_EQ(c.sum(3,4), 7);

EXPECT_EQ(c.mul(1,2), 2);

EXPECT_EQ(c.mul(3,4), 12);

}Remember we mentioned Clang comes with nice tools? Here are 2 examples.

Address Sanitizer

Address Sanitizer is a fast memory error detector. It consists of a compiler instrumentation module and a run-time library. The tool can detect the following types of bugs:

- Out-of-bounds accesses to heap, stack and globals

- Use-after-free

- Use-after-return (to some extent)

- Double-free, invalid free

- Memory leaks (experimental)

Typical slowdown introduced by Address Sanitizer is 2x which is way faster than Valgrind.

int main() {

int array[10];

array[10] = 123;

}In this example we’re making an out-of-bounds access. Without Adress Sanitizer many times this error goes unnoticed. However when compiling with Address Sanitizer support we get the following warning:

[32, 72) 'array' <== Memory access at offset 72 overflows this variable

Thread Sanitizer

ThreadSanitizer is a tool that detects data races. It consists of a compiler instrumentation module and a run-time library. Typical slowdown introduced by ThreadSanitizer is about 5x-15x. Typical memory overhead is about 5x-10x.

int main()

{

uint64_t counter = 0;

auto incr = [&] () {

for (auto i : boost::irange(0,1000000)) {

++counter;

}

};

std::thread t1(incr);

std::thread t2(incr);

t1.join();

t2.join();

std::cout << counter << std::endl;

return 0;

}In this example there’s a race condition and Thread Sanitizer gives us the following warning:

WARNING: ThreadSanitizer: data race (pid=79195)

Write of size 8 at 0x7fffa50a2a60 by thread T2:

Previous write of size 8 at 0x7fffa50a2a60 by thread T1:

To fix the previous exam[le we can make incr atomic or use a mutex.

Facebook Folly

Folly is a collection of reusable C++ library artifacts developed and used at Facebook.

Some examples are faster replacements for std::string and std::vector and a useful benchmarking module:

BENCHMARK(copy) {

vector<uint64_t> v;

v.resize(128*1024*1024);

FOR_EACH_RANGE (i, 0, 1) {

vector<uint64_t> v2(v);

}

}

BENCHMARK(move) {

vector<uint64_t> v;

v.resize(128*1024*1024);

FOR_EACH_RANGE (i, 0, 1) {

vector<uint64_t> v2(std::move(v));

}

}

int main() {

runBenchmarks();

}Google Performance Tools

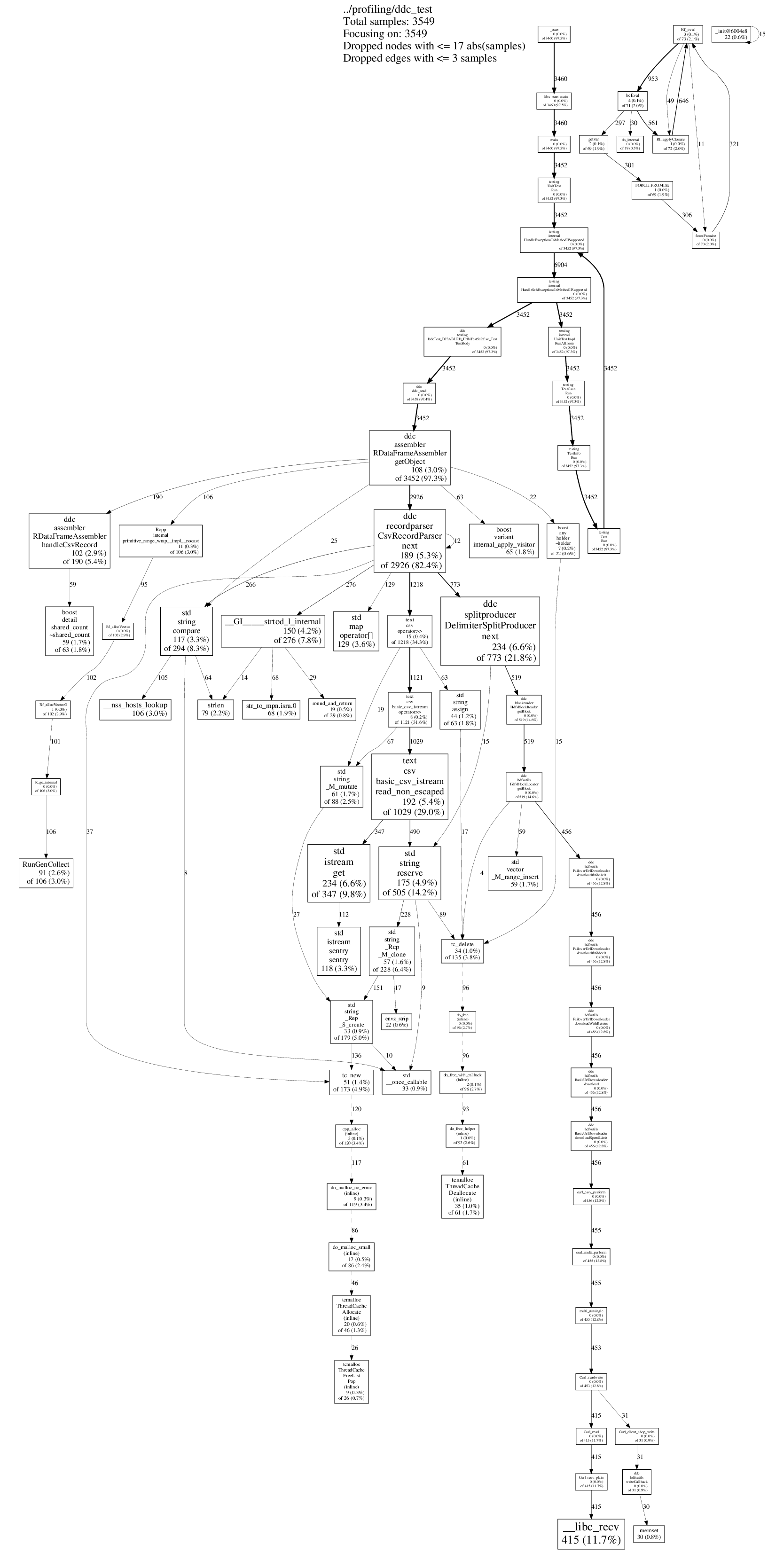

Gperftools is useful to find out where the program spends cycles. It accounts for network and IO time as well. You can generate a profile using:

$ CPUPROFILE=/tmp/$PROFILENAME.prof LD_PRELOAD=/usr/local/lib/libprofiler.so:/usr/lib/libtcmalloc.so $BINARY $ARGS

$ pprof --gv $BINARY /tmp/$PROFILENAME.prof

This is an example profile:

Linting

cpplint.py gives a lot useful warnings about code style and common c++ errors:

$ cpplint.py <files>

Docker

Docker gives you a single environment in which you have total control over dependencies and versions. And the best part is that the environment will be the same (or very similar) in development and production.

To “Dockerize” an application all you need to do is to create a Dockerfile. For static binaries this is really simple:

// Dockerfile

FROM centos

COPY myapp /tmp/

CMD /tmp/myapp

We can build the Docker image with:

$ docker build -t jorgemarsal/myapp:0.0.1 .

And run it with:

$ docker run --name myapp jorgemarsal/myapp:0.0.1

Continous Integration (Jenkins)

All the tooling presented before should be integrated with CI:

- Check code for memory and threading problems (asan/tsan)

- Run test suites (gtest)

- Check for style, linting

- Coverage

- Metrics/ track improvements

- …

Conclusions

In this post we’ve described a few useful c++ tools and techniques. Other topics that are fundamental but we didn’t discuss are:

- Mastering a scripting language (e.g. Python)

- Mastering the command line

- Mastering your IDE

- Automating everything

- Shortening release cycles (e.g. via continuous delivery)