100000-foot view of a modern web service

In this post we’re going to explore how to deliver a modern web service. To make things clearer we’re going to use a OCR service as an example. All the code is available on Github.

WebOCR extracts text from user uploaded images using a technique known as OCR. Users provide the image information (for now just the URL) and the service downloads the image, extracts the text and sends the result back to the user.

Architecture

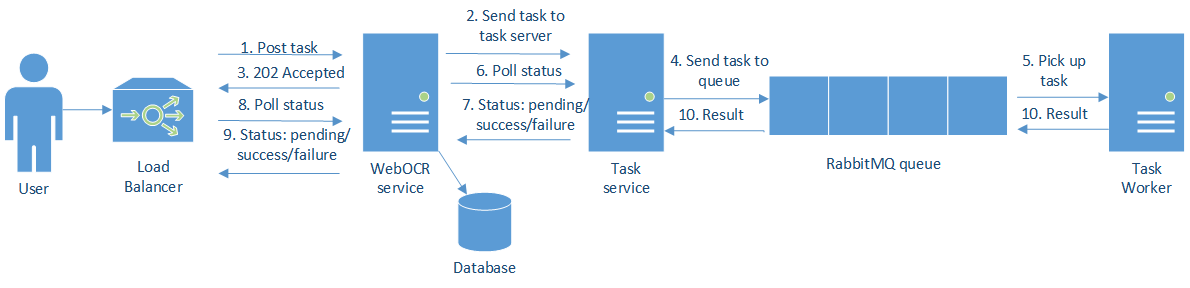

The architecture is shown in this picture below:

There are 2 main elements:

- The WebOCR service provides a restful API for extracting text from images.

- The task server and associated workers perform the actual OCR processing.

The basic workflow is:

- Users post a request with the image information.

- The WebOCR service sends the task to the task server and …

- … replies with a 202 Accepted code and a link to check the task progress.

- The task server sends the task to a queue (RabbitMQ in this case).

- The worker picks up the task from the queue.

- The server polls the task server periodically to update the task status and stores that information.

- The client can also access this information through the

/queueendpoint in the WebOCR service. - Eventually the task will succeed or fail. If the task succeeds the client will get redirected to the result. If it fails the client can retrieve the failure cause from the /queue endpoint.

- Both the client and the web server have timeouts and consider the task failed if they don’t receive a response in a timely manner.

This is an example exchange:

curl -v -H "Content-Type: application/json" -X POST \

-d '{"url":"http://localhost:1234/static/ocr/sample1.jpg"}' \

http://localhost:1234/api/v1/services

...

HTTP/1.1 202 Accepted

Content-Location: /queue/7bc6c484-df47-4cb6-b254-17b770b52060

….

The server replies with a 202 code and a URL to query the task status. If we access that URL and the task is still pending we’ll get a 200 ok and info about the task. When the task is done we’ll get a 303 and a link to the newly created resource:

curl -v http://localhost:1234/queue/abb5fbbf-9519-4d21-af23-e3a7da1ca480

….

HTTP/1.1 303 See Other

Location: /api/v1/service/90

…

Let’s get the result:

$ curl -v http://localhost:1234/api/v1/service/90

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

{

"result": "THINGS YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOU ...

... neiraviers common In\n\n",

"state": "SUCCESS",

"url": "http://localhost:1234/static/ocr/sample1.jpg"

}

We also have a websocket channel to send real time information of the task progress to the frontend.

The next sections go into more detail on how all of this is implemented.

Backend

The backend is a Tornado app that implements the restful API. There aren’t any blocking operations. We either use event-loop aware functionality (like Tornado’s AsyncHTTPClient or run the task in a different thread with the @run_on_executor decorator. By using this design the server can handle many concurrent user connections.

@run_on_executor

def _on_executor(self, fn, *args, **kwargs):

"""Execute the given function on another thread"""

return fn(*args, **kwargs)

@gen.coroutine

def f():

http_client = AsyncHTTPClient()

response = yield http_client.fetch("http://example.com")

Database

Choosing the right database is probably one of the most important decision in a web project. In this case, since the performance requirements are modest, we don’t need a database cluster and we can live with a single node and snapshot backups. In this situation we can pretty much do whatever we want and we’ve chosen MySQL. When the performance requirements are higher then we need to consider other solutions and keep in mind the associated performance and consistency tradeoffs.

As mentioned earlier the backend stores the state in a MySQL database but instead of having a fixed schema we have a schemaless design. The original idea comes from Friendfeed’s schemaless design and the implementation (with minor modifications) comes from Evan Klitzke.

In this design we store compressed pickled python dictionaries that can hold arbitrary data, making schema evolution simple. Note that this idea is from 2009 when NoSQL offerings weren’t as mature as today. Probably nowadays we’d be better off using something like Mongo. Storing and querying the database is done like this:

row = self.db.put(dict(url=service['url'], state='PENDING'))

rows = url_index.query(c.url == url)

Task server

We’ve decided to offload the actual computations to a task server. This way we can keep a simple WebOCR service and scale the task server independently if the load increases.

The task server exposes another REST API to send tasks to Celery. Celery is an asynchronous task queue/job queue based on distributed message passing. The workflow is quite simple. The WebOCR service posts tasks to the task server. The task server sends those tasks to a queue (RabbitMQ in this case) and on the other end, one or more task workers pick up the tasks.

Advice for developing backend code

Giving a complete overview of all the things to keep in mind when developing backend SW is out of scope for this post. However we’ll just give a few pieces of advice.

We decided to develop the service in Python because it’s a language we’re pretty familiar with. Developing in python is really fast due to its dynamic nature and it comes with libraries for almost everything. Node.js could have been a good option as well. If type safety or performance are important considerations then Go would have been a better alternative.

A lot of advice about Python itself can be found in the fantastic book Effective Python.

One of the most important things to do when developing software is having good testing. One rule that I find particularly useful to increase confidence is having a high test coverage. Keep in mind that high coverage is not enough though. It’s important to design a very comprehensive test plan. Otherwise you can have 100% coverage but ignore a lot of real-world cases. A tool that works well is pytest-cov. You can get coverage numbers using this command:

py.test --cov=webocr --cov-report=html

As an example if we want to test a call to a remote service we should at least test a couple scenarios:

- Service works ok

- Service not running

- Service returns HTTP errrors

- Service returns 200 ok but response data is malformed.

To easily test all those error conditions we can mock the service using somethind like this:

class App(object):

def __init__(self, service):

self.service = service

def do(self):

try:

self.service.do(something)

except ServiceError as e:

handle_exception()

def test_normal():

“”” Normal service “””

app = App(service)

def test_error():

“”” Mock service that triggers all the error conditions “””

app = App(mock_service)

Correctness is absolute necessary but you should also take a look at the performance of the service. You can use something like Jmeter for that.

Finally a linting tool like flakes8 can point common errors and style issues.

I recommend having testing, linting and other tooling as part of the CI process both on the client (via Git hooks) and on the server (with something like Jenkins).

Frontend

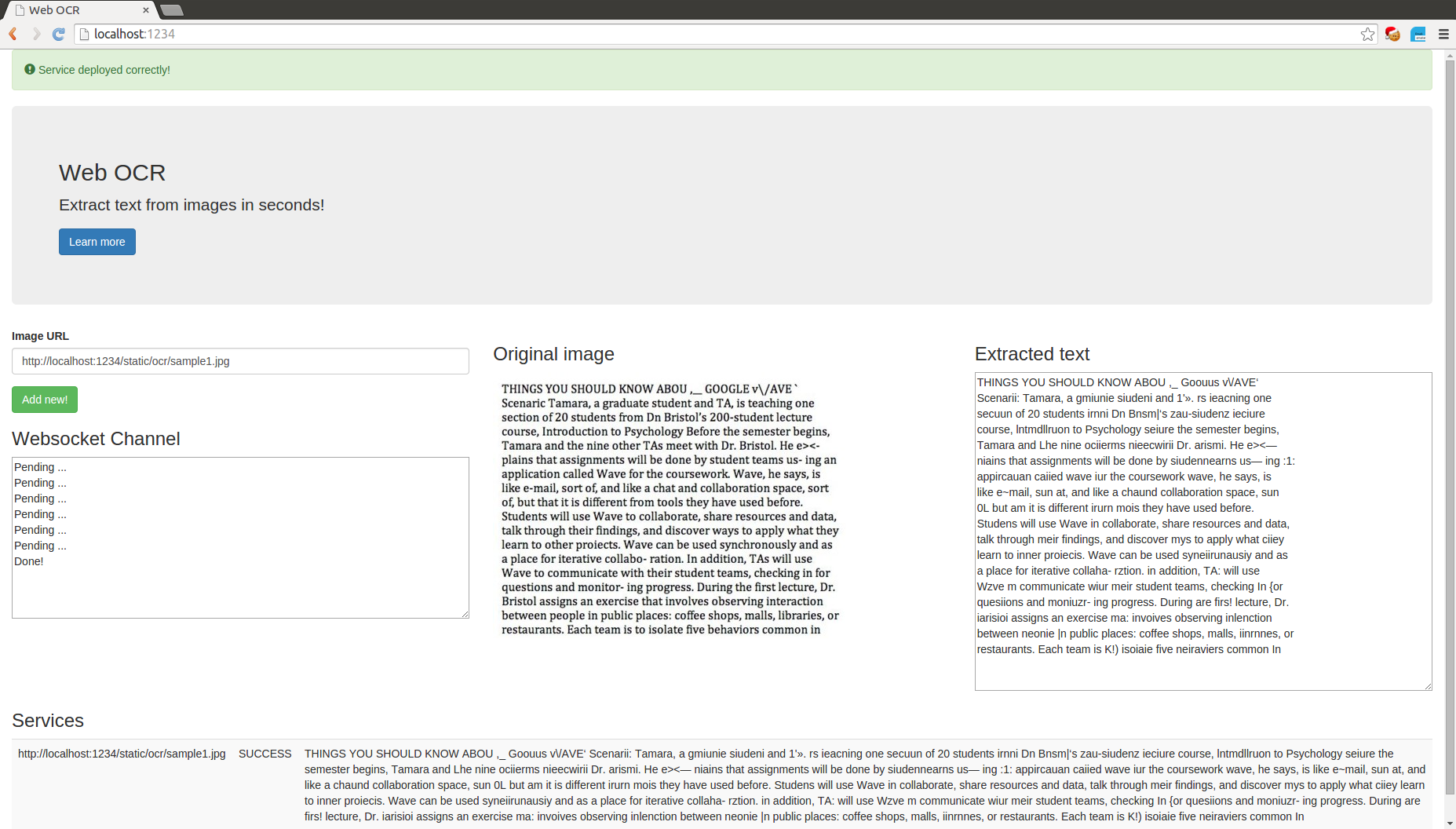

We’ve created a simple webpage to submit new tasks and to display the status of pending/finished tasks (see pic below). On the left hand side we have a form to submit the image information. In the middle we display the original image and on the right the extracted text. We also have a websocket channel to receive real-time progress updates.

I’m by no means a frontend expert. I just know the minimum HTML, CSS and JS to get by. Having said that, it pays off to organize the code properly. For JS we follow the MVC pattern. The important point to remember is that the model and the view don’t talk directly, they always go through the controller.

Infrastructure

Developing the software is just half the problem Then you have to reliably run it in production. In this section I’m gonna talk about 2 great pieces of software that we use and help greatly: Docker and Kubernetes.

Docker gives you a single environment in which you have total control over dependencies and versions. And the best part is that the environment will be the same (or very similar) in development and production. We recommend dockerizing every service.

The other piece of the puzzle is kubernetes. Kubernetes is an open source orchestration system for Docker containers that provides fault tolerance and high availability. One of the main abstraction in Kubernetes is the Replication Controller. You can specify how many pods (collection of containers) you want to have running and kubernetes will enforce that. Kubernetes performs health checks and automatically restarts the pods if there are errors. Another interesting feature is the ability to increase the number of pods based on load. That way you can scale your service up or down based on load. In this example we can increase the number of task workers if the load is high and reduce it to save costs if the load decreases.

The other important abstraction is the service. Services provide discoverability and have neat features like automatic load balancing of the traffic between pods. Kubernetes also comes with solutions for logging and monitoring.

Conclusion

With this we conclude this blog post. We hope the ideas presented here will help you with your own designs. The complete code is up on Github.